Research Overview

Below, I provide a slightly more elaborate (and mostly self-contained) overview of my research. Still, the best way to learn about my research is to read my articles. You can find them on the Publications page.

Background

Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA)

I work on the data analysis pipeline for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) (NASA), scheduled for launch in the mid-2030s (ESA). LISA will be sensitive to gravitational waves from galactic binaries, supermassive black hole mergers, and extreme-mass-ratio inspirals (EMRIs) in which a stellar-mass black hole orbits a supermassive one (LISA Collaboration). EMRIs are my primary focus.

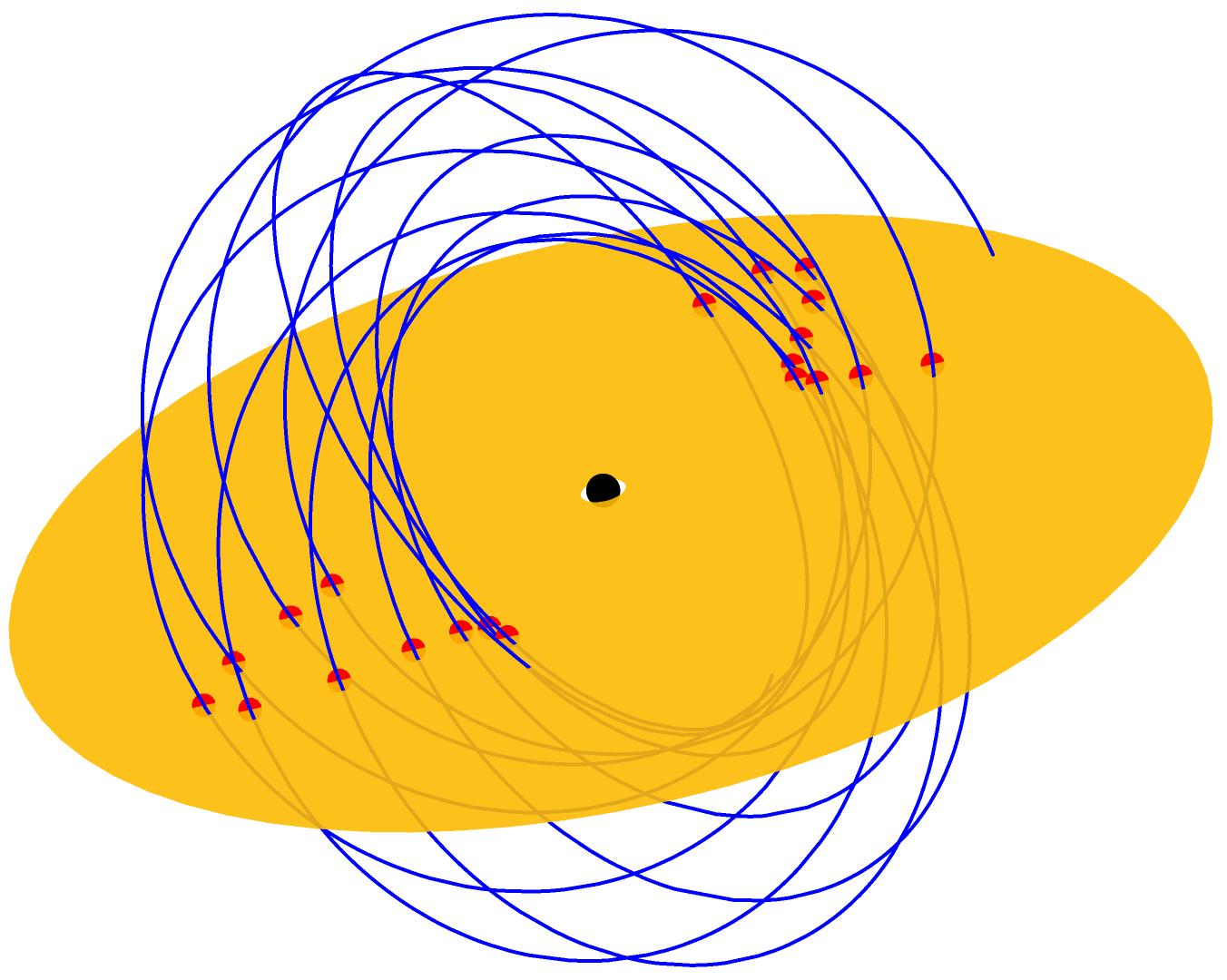

Extreme-mass-ratio inspirals (EMRIs)

Gravitational wave signals from EMRIs will last in the LISA band for years, allowing us to map the curvature of spacetime around supermassive black holes and test General Relativity (GR) with high precision. Their long inspirals also make them sensitive to environmental effects, such as migration torques from accretion disks.

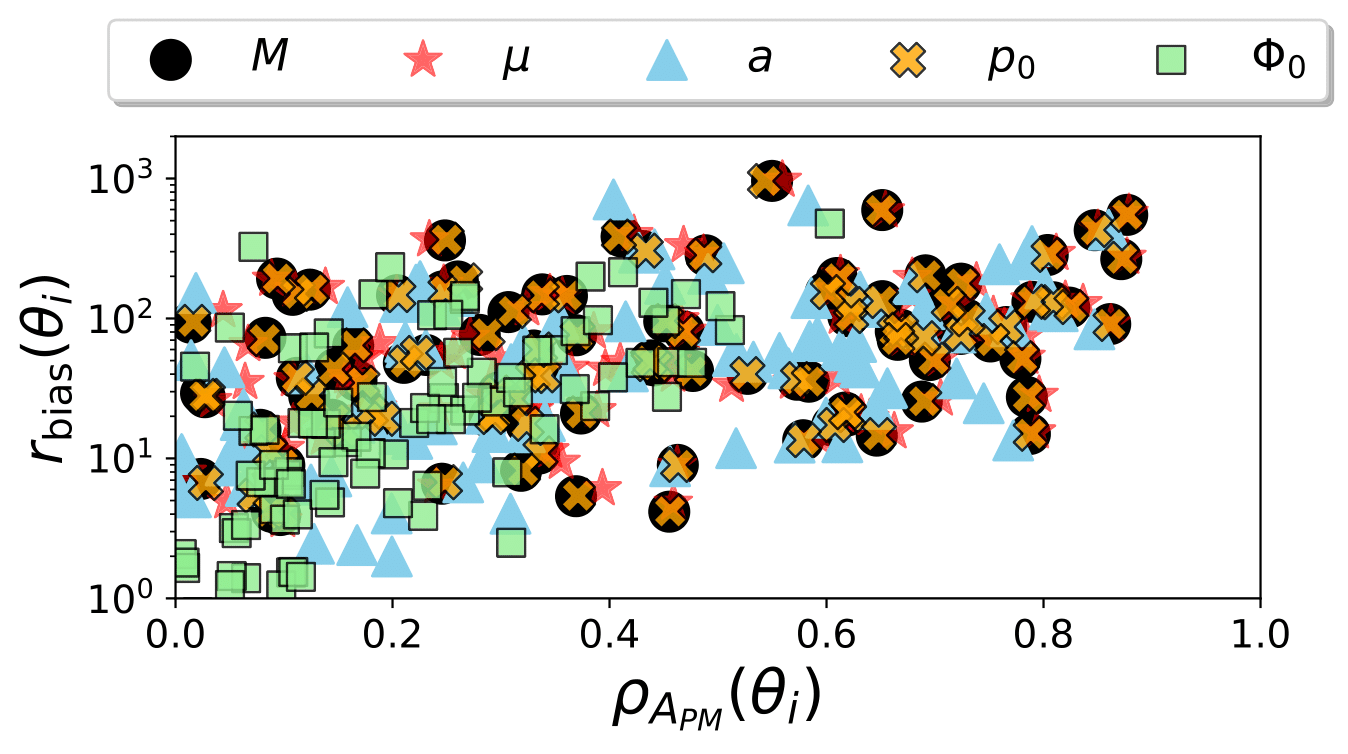

Measurability of “Beyond-Vacuum-GR” effects in EMRIs

Many proposed environmental and beyond-GR effects are added perturbatively to the EMRI’s dynamics, see e.g. Kocsis et al. (2011), Barausse et al. (2014), and Yunes and Pretorius (2009). Using a generic mathematical framework, we show in our work (Kejriwal et al. (2023)), that such setups can cause strong parameter correlations when multiple effects are measured simultaneously, worsening inference. On the other hand, excluding such effects from the analysis can significantly bias the inferred parameters (by \(\gtrsim 10\sigma\)).

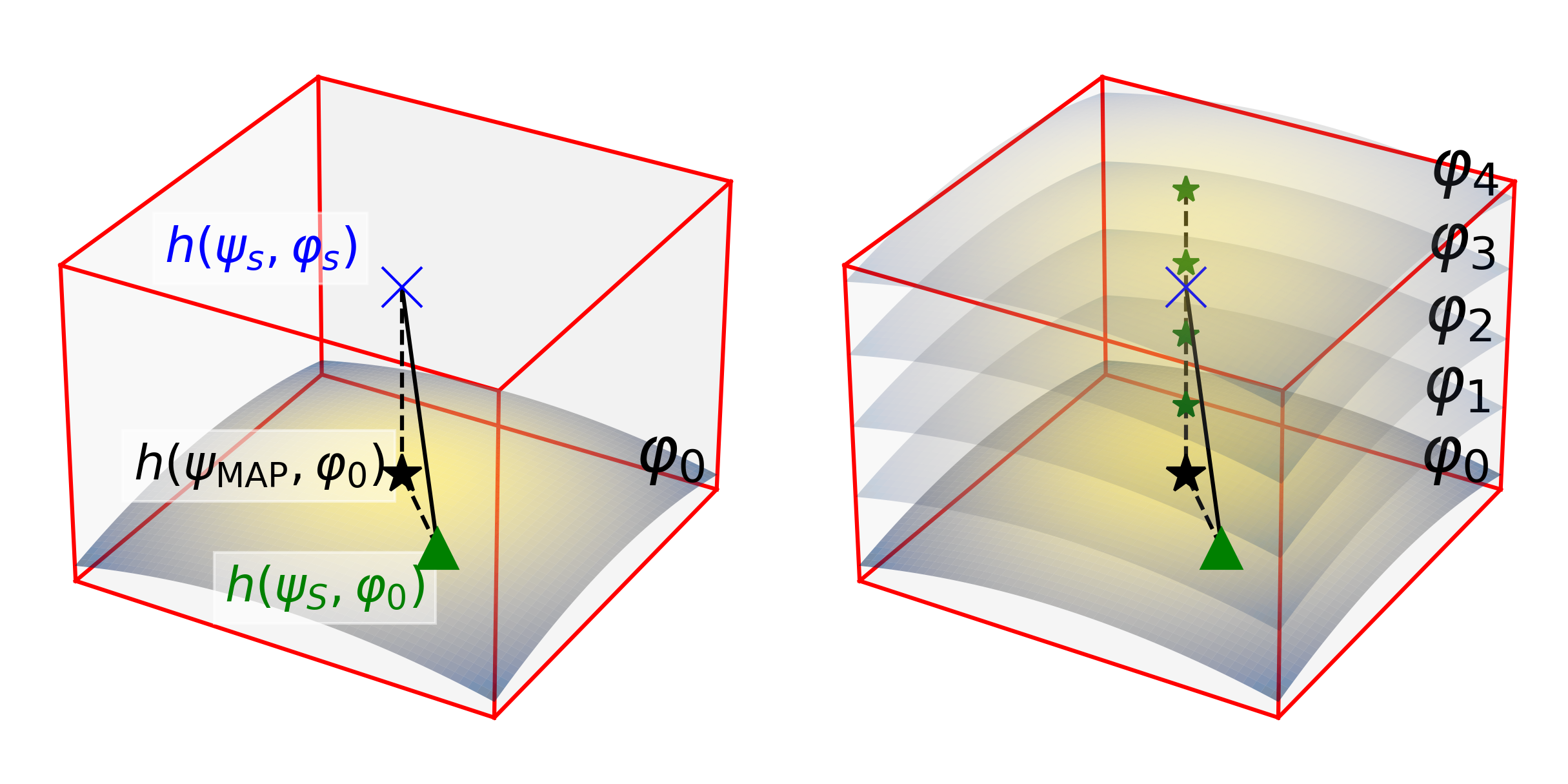

Bias-Corrected Importance Sampling

The cost of inference under a single hypothesis can be overwhelming, especially in the context of the LISA global fit pipeline. It is thus impractical to perform tests of environmental and beyond-GR modifications using conventional methods. In our work (Kejriwal et al. (2025)), we proposes bias-corrected importance sampling, which can consistently and inexpensively obtain samples from the posterior in alternative hypotheses, given just the posterior samples under vacuum-GR.

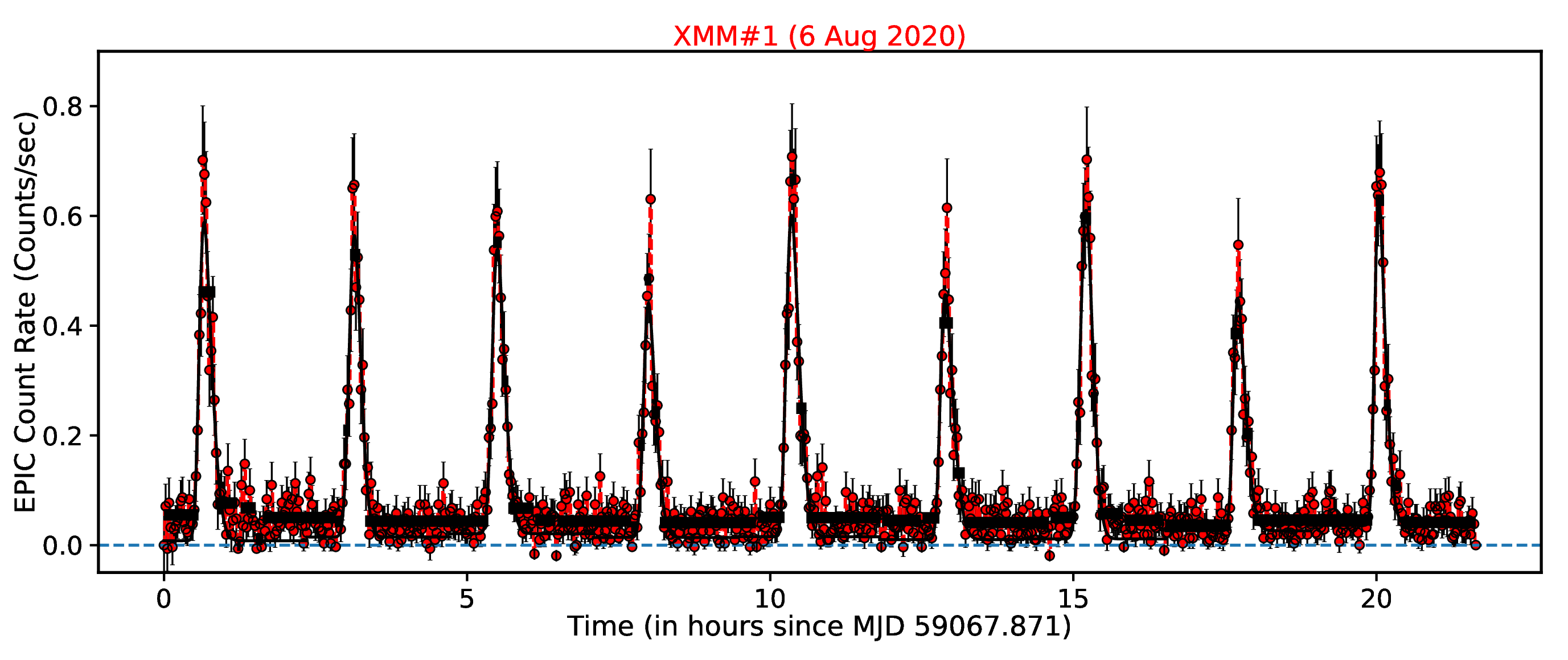

Electromagnetic Counterparts of EMRIs

Quasi-periodic eruptions (QPEs) are low-frequency (\(\sim 10^{-4}\) Hz) soft X-ray band signals, and are emerging as candidate electromagnetic counterparts of EMRIs with accretion disks, see e.g. Linial and Metzger (2023). This poses an exciting prospect of multimessenger astronomy with EMRIs. In our work, (Kejriwal et al. (2024)), we analyzed the prospect of simultaneously observing EMRIs in the X-ray band and as GWs. Such sources open a new avenue of multimessenger astronomy with EMRIs. We also analyzed RE J1034+396, a QP’O’ (where ‘O’ is now for ‘oscillations’). We found that REJ may host an orbiting compact object of mass \(\approx 47 M_\odot\). We also estimated that there is a \(\approx 25\%\) probability that REJ may be detected by LISA.

Developing Waveform Models and Data Analysis Tools

There are multiple ongoing projects that I am actively contributing to:

-

Waveform modeling: We are developing the

SuperKludge: a hybridized waveform model that can be used for practical data analysis of EMRIs. -

FastEMRIWaveforms (FEW): I am involved in the development ofFEW v2.0and its data analysis implications. The pre-print is now available here. -

StableEMRIFisher (SEF): I am the creater ofStableEMRIFisher (SEF), a package to generate fast and robust information matrices for EMRIs.SEFis available publicly on Github.

© 2025 Shubham Kejriwal